Miner’s Union Hall: A Working Landmark on the Comstock

Guest Contributor: Audie Robinson

On North B Street, where Virginia City’s commercial blocks climb the hillside, the Miner’s Union Hall stands much as it has for nearly a century and a half, solid, purposeful, and in use. Built of brick in 1876, the two-story hall has never been a relic waiting to be rediscovered. From the height of the Comstock mining era to the present day, it has remained a place where people gather, organize, and invest in their community.

When the Comstock Lode was discovered in 1859, Virginia City grew almost overnight into one of the most important mining centers in the American West. Beneath the city’s streets, miners worked deep underground in conditions that were dangerous and unpredictable. Heat, poor ventilation, flooding, cave-ins, and industrial accidents were part of daily life. As mining became increasingly capital-intensive and ownership shifted to large, often absentee-controlled corporations, miners found themselves with little individual leverage over wages or working

conditions.

Organization emerged as a practical response. In 1863, miners formed the Miner’s Protective Association of Storey County, followed a year later by the Storey County Miners’ League. These early organizations sought to standardize underground wages at four dollars per day and to assert collective bargaining power within an increasingly industrialized mining economy. In 1864, miners in Virginia City and Gold Hill staged coordinated demonstrations, among the earliest large-scale labor actions in the western mining industry.

Those early efforts were short-lived. A mining depression in 1864–1865 weakened the League, and mine owners blacklisted union members. Territorial Governor James W. Nye went further, ordering federal troops from Fort Churchill to Virginia City to suppress union activity. The Storey County Miners’ League collapsed, but the lessons endured. Miners learned that lasting success required not only collective action, but political awareness, community support, and permanent institutional footing.

By the late 1860s, miners reorganized with greater durability. The Gold Hill Miners’ Union formed in 1866, followed by the Virginia City Miners’ Union on July 4, 1867. These organizations succeeded where earlier efforts had failed, enforcing the four-dollar daily wage and later securing the eight-hour workday in 1872. On the Comstock, organized labor became a stabilizing force in an industry defined by risk.

As the Virginia City Miners’ Union expanded its role beyond wages to include mutual aid, education, and civic participation, the need for a permanent headquarters became clear. In 1870, a parcel on B Street was formally conveyed for the use and benefit of the union, establishing the site as a purpose-built labor institution. That first building was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1875, which swept through Virginia City and reshaped much of its commercial and institutional

core.

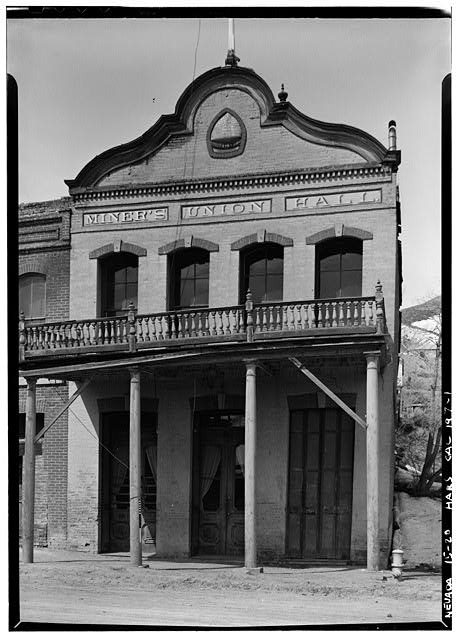

The following year, the miners rebuilt, this time in brick. The new Miner’s Union Hall rose on the same parcel in 1876 at a reported cost of approximately $15,000. Its construction reflected post-fire priorities that emphasized masonry and fire resistance. The building’s curving brick false front concealed a gable roof, a common local practice that reduced fire risk while maintaining a consistent streetscape. Tall upper-story windows, steel fire doors at street level,

and a prominent porch and second-story balcony gave the hall an unmistakable institutional presence. A metal beehive crowned the parapet, symbolizing communal labor and shared responsibility.

Inside, the building quickly became one of Virginia City’s most important civic spaces. The ground floor served as a large assembly hall for meetings, lectures, and social events. Upstairs, the union established the Miners’ Union Library in 1877, appropriating $2,000 from union funds. By the early 1880s, the library contained approximately 2,200 volumes and was widely described as the city’s only public library. Union members enjoyed free access, while non- members were welcomed for a small monthly fee. Reading rooms and chess rooms shared the upper floor, reinforcing the hall’s role as a center for education, self-improvement, and social

life.

As the Comstock’s great bonanza years faded after the late 1870s, organized mining labor gradually lost influence. Yet the Miner’s Union Hall did not fall quiet. Meetings continued, and the building remained a familiar gathering place. In 1926, ownership passed to the Comstock Aerie 523, Fraternal Order of Eagles, reflecting a broader regional pattern in which former labor halls were adopted by fraternal organizations as mining declined. The transition did not end the building’s institutional life; it extended it.

Under Eagle stewardship, the hall has continued to function as a meeting place and social center, preserving its long-standing role in Virginia City’s civic fabric. Today, Comstock Aerie No. 523 meets monthly on the third Thursday at 7 p.m., maintaining an unbroken tradition of regular use that stretches back to the nineteenth century.

That continuity shapes the Aerie’s approach to restoration. The Miner’s Union Hall is not treated as a static monument or a frozen artifact. Instead, restoration is understood as an intentional, forward-looking effort, one that respects historic materials and character while ensuring the building remains safe, functional, and relevant. The goal is not simply to preserve a structure, but to sustain a working hall.

Public engagement is central to that mission. By sharing the building’s history, its roots in organized labor, its role in worker education, and its uninterrupted use, the Aerie seeks to build broader understanding of why the Miner’s Union Hall matters. Financial contributions, new memberships, and community advocacy all play a role in carrying this work forward, just as collective investment sustained the hall in earlier generations.

The Miner’s Union Hall has always been a place where people come together. From miners organizing for fair wages, to readers browsing library shelves, to Eagles gathering for monthly meetings, the building has adapted while remaining true to its purpose. As a working landmark on the Comstock, its future, like its past, depends on shared responsibility and continued participation from the community it serves.

For more information, follow the Comstock Aerie 523, Fraternal Order of Eagles on Facebook, write to P.O. Box 80, Virginia City, Nevada, or join us at the Miner’s Union Hall, 36 North B Street, Virginia City, on the third Thursday of each month around 7 p.m.