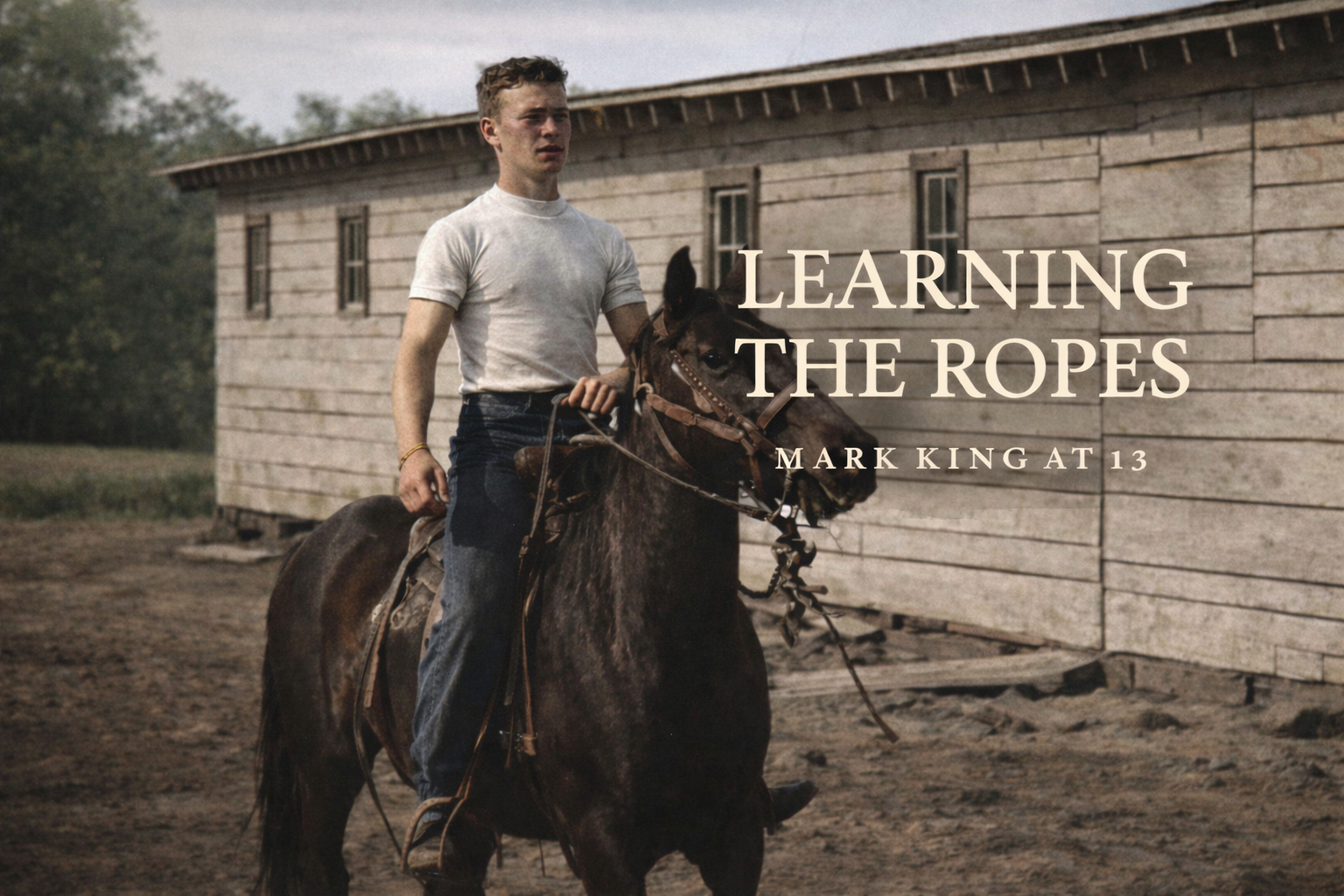

King's Corner: Learning the Ropes

The flashing airplane beacon in Stagecoach caught my father’s attention the first time he flew over this area in the 1960s. Mark King was working with the film crew of Bonanza, teaching horses and actors how to work together safely during stunts. While most outdoor filming took place at the Ponderosa near Lake Tahoe, the other main setting was Virginia City, where Mark somehow became an honorary marshal—proof that persistence occasionally beats qualifications.

He settled where he could see that beacon blinking at night—and, beyond it, the large “V” on the mountainside.

The pull of the Old West is both real and imagined: old mining towns, wide-open spaces, wild horses, and land that once promised a future to anyone willing to work for it. There’s also the chance to find—or reinvent—yourself, the way Samuel Clemens did when he rented a room on C Street and became Mark Twain. (Reinvention was apparently easier before social media.)

The Comstock has always been a place for people willing to try.

The older I get, the more convinced I am that very little in life is accidental. Doors open. Doors close. And if you’re paying attention, you begin to recognize which answer you’ve been given. My dad seemed to have a knack for that—though he didn’t start out knowing much at all.

Years earlier, at thirteen, Mark was earning money doing combine harvesting across North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming. It wasn’t glamorous work, but it paid, and it put him around people who knew how to do things he wanted to learn. One of them was a man named Ken, who also worked rodeos.

Ken offered to teach Mark how to be a rodeo hazer.

That didn’t sound impressive at first—mostly because Mark didn’t yet know what it meant. A hazer rides alongside the bulldogger, keeping the steer perfectly positioned so the bulldogger can jump from his horse, grab the horns, and wrestle the animal to the ground. In practice, it means riding close to danger so someone else can succeed—a role that builds character quickly, whether you asked for it or not.

“A good hazing horse makes or breaks a bulldogging horse,” Ken explained. “And your bulldogging horse is only as good as your hazing horse.”

No pressure.

Once the bulldogger nods, the steer is released. The hazer rockets out of the gate, bookends the steer, keeps it straight, and hopes everyone involved has made good life choices. It’s widely considered the hardest job in steer wrestling, which made it exactly the right place for a teenager to start—especially one wise enough to know he had plenty to learn and no room for heroics.

More than anything, hazing is about trust. The bulldogger has to believe the hazer will be there, even when he can’t see him. Ken trusted Mark completely. That trust mattered. In life, we all need someone we can have faith in—someone steady at our side—especially when the ground gets rough and the moment gets fast.

They worked rodeos from Texas to the Canadian border. Ken did the bulldogging. Mark rode alongside, learning timing, restraint, and what happens when confidence runs ahead of skill. Over time, borrowed confidence slowly became earned confidence, which is far more durable and considerably less noisy.

They qualified for the big ones—the Days of ’76 and the Calgary Stampede—sharing winnings along the way. Ken eventually got hurt and had to withdraw. Mark kept going—but that’s a story for next time.

What mattered just as much as the rodeos was what those years taught him away from the arena. Riding alongside danger day after day has a way of clarifying things. You learn that courage without judgment is recklessness, and judgment without courage is paralysis. The trick, as it turns out, is learning when to move—and when to wait.

Years later, standing in Virginia City with that beacon flashing in the distance, that balance makes sense.

By then, Mark was also a man of books. That side of him had been developing quietly all along, often in solitude while working remote properties and mending fences. Every few weeks supplies arrived; otherwise, he was alone. Instead of idling, he read—Kipling, Shakespeare, Scripture. He memorized poems, Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be,” and long passages of the Bible. It was a thorough education, even without a syllabus.

It wasn’t a retreat from adventure. It was its companion.

Those hours reading weren’t about escape; they were about attention—learning how to think deeply before acting decisively. The same instinct that kept him steady beside a charging steer taught him to pause with a book and weigh words carefully.

Once, he told me about a literary magazine that asked writers three questions. What is the most beautiful word in the English language? Answers varied. What is the most misused word? Nearly everyone said “yes.” And what is the most useful word? The overwhelming answer was “no.”

That insight fits his life well. Adventure isn’t recklessness. It’s attentiveness. Knowing when to ride forward, and when to hold back. Doors open. Doors close. And you don’t always know which answer you’ve been given until you get out on the range.

But if you’re listening—if you’re willing to learn the ropes—you discover that confidence grows, trust deepens, and your direction becomes clear.

Jeff Headley is pastor of the Dayton Valley Community Church, and a storyteller who blends humor, honesty, and hope. His weekly column reflects on resilience, grace, and the surprising ways faith shows up in ordinary life.