King's Corner: The Luck of Roaring Camp

Roaring Camp was not the sort of place where good news happened. In 1850, if a gunfight broke out, nobody paused their card game long enough to notice—French Pete and Kanaka Joe once shot each other clean through right in front of Tuttle’s grocery, and someone simply leaned over the bodies to pick up a dropped poker chip.

So naturally, when a crowd gathered outside Cherokee Sal’s cabin one evening, the men knew this was something different. Nobody was yelling. Nobody was shooting. Nobody was cheating. They were whispering. And in Roaring Camp, whispering meant something downright extraordinary. A few fellows even took off their hats, which was suspicious behavior for men who slept with them on.

Cherokee Sal was the only woman in camp, and she was in rough shape—bringing a child into the world with no midwife, no doctor, and nothing but hard rock, harder men, and some withered pine boughs for comfort. Even the gamblers felt uneasy. Sandy Tipton, who usually had an ace hidden somewhere on his person, forgot entirely that he was cheating and muttered, “Rough on Sal.”

Inside that cabin, a miracle was attempting to happen in the least miraculous place in the Sierra Nevada.

“Stumpy,” Kentuck said, nudging the man with the sort of tone one uses when volunteering someone else. “You’ve had experience with families. Such as they were.”

Stumpy sighed, flicked the ash off his pipe, and stepped inside to help. The door closed. The entire camp sat down outside, and—for the first time in history—Roaring Camp waited quietly. Someone tried to place a bet on the outcome, but even Oakhurst the Gambler told him to “show some respect for Providence,” which startled everyone present.

The moon climbed up the hill. The river hushed its roar. Even the pines held their breath.

Then it happened:

A cry.

Small. Sharp. New.

It sliced through the smoke, the murmurs, the moaning wind—and every rough miner in that clearing froze like he’d seen an angel. You could’ve heard a gold flake drop.

The men burst into cheers, and a few even fired pistols in the air, until someone reminded them that the mother was still in peril. But despite their good-hearted noise, Cherokee Sal slipped away within the hour, leaving behind a child and a camp full of men who suddenly felt more lost than usual.

They all looked at Stumpy.

“Can he live?” someone asked.

Stumpy scratched his chin. “Only female help in camp is Jinny the mule,” he said.

Jinny was not flattered by the assignment, but she served with distinction. After all, she’d carried half the town’s mistakes on her back already; one more hardly changed her workload.

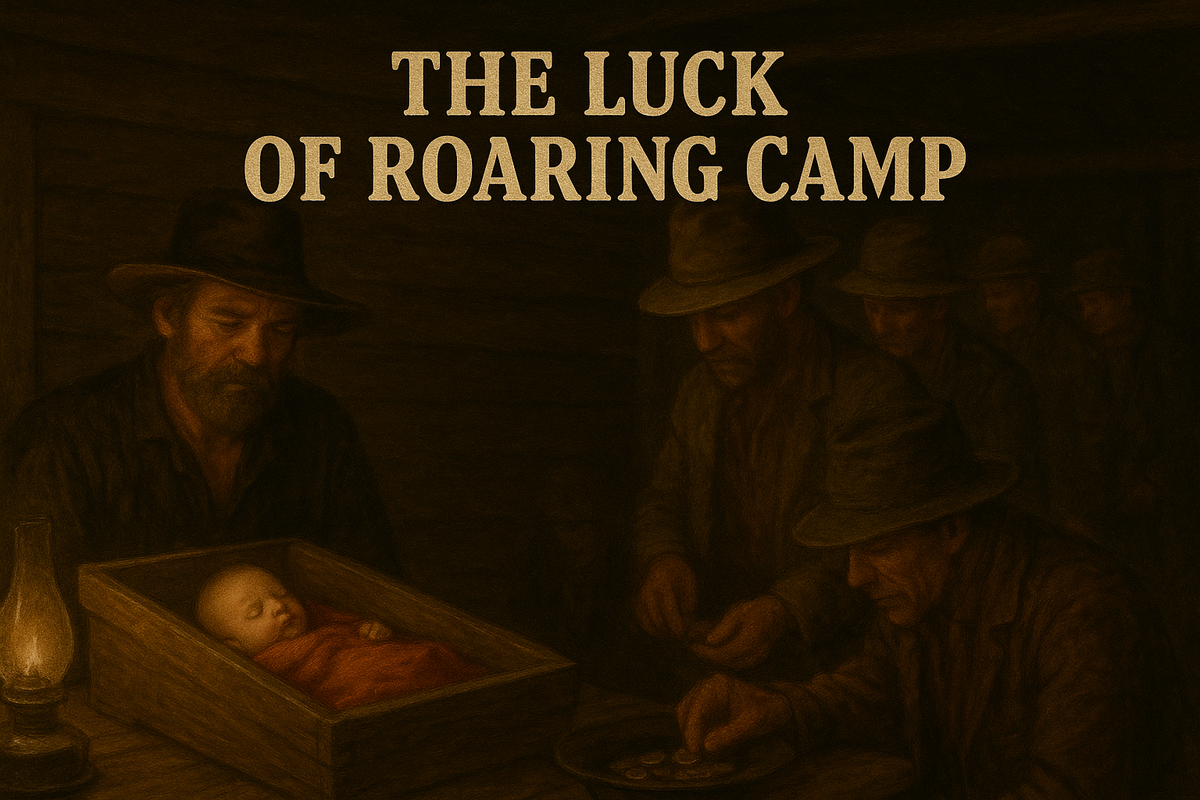

Within a few hours, Stumpy opened the cabin door and the men lined up single file to meet their newest resident. They filed in like miners approaching a gold weigh-in, hats off, voices lowered, something like reverence settling over them.

On the pine table lay a candle-box, cleaned up and lined with red flannel. Inside it slept a baby—small, new, and shining a little like the first ray of dawn slipping over a mountain ridge.

“Tiny thing,” someone whispered.

“Barely bigger’n a derringer,” another murmured.

Yet each man dropped something into the offering hat—gold flakes, a silver tobacco box, a lady’s embroidered handkerchief no one asked Oakhurst the Gambler to explain, and even a Bible (suspected of being stolen, though the Lord may have let that pass under the circumstances). One fellow even contributed a single spur, explaining the baby “might as well start life with direction.”

Then came the moment that changed the camp forever.

Kentuck—a man with the build of a mustang and the manners of one too—leaned over the candle-box. The baby grabbed his finger.

Kentuck froze. His weather-beaten face reddened like he’d been caught being kind.

“Well, I’ll be,” he muttered.

“He rastled with my finger… the little cuss.”

But he said it softly, like a man saying a prayer.

Something shifted that night.

Something subtle.

Something holy.

You see, Roaring Camp wasn’t Bethlehem, and these men sure weren’t shepherds. But the way they gathered around that child… the way they fell quiet in his presence… the way that rough cabin glowed with lantern light and hope—it all felt strangely familiar. Like another night long ago when unexpected people found themselves kneeling beside a newborn who had no business arriving in such humble surroundings.

The camp improved almost instantly. Roaring stopped roaring. Men quit swearing near the baby. They washed their faces. Some even washed their shirts. Tuttle’s grocery imported mirrors because the men suddenly cared what they looked like. A few even trimmed their beards, though the results varied wildly.

They built the child a better cabin, then fixed up their own. Flowers appeared. Carpets. Clean floors. The kind of things nobody had ever bothered with because—well—what was the point?

But now there was a point.

They named him Luck because what else do you call a baby who makes a hard camp gentler, cleaner, quieter, kinder?

A child who brought peace to a violent place.

Light to a dark gulch.

Hope where hope had no business growing.

And in that rough mining camp nestled in the Sierra Nevadas, the men of Roaring Camp learned—almost by accident—what the shepherds learned long ago:

Sometimes God sends a miracle in swaddling clothes,

into a place that deserves Him least,

to change it most.

May this Christmas remind us that light still slips into dark places, grace still arrives in rough cabins, and hope is still born where no one expects it.

Jeff Headley is pastor of the Dayton Valley Community Church, and a storyteller who blends humor, honesty, and hope. His weekly column reflects on resilience, grace, and the surprising ways faith shows up in ordinary life.