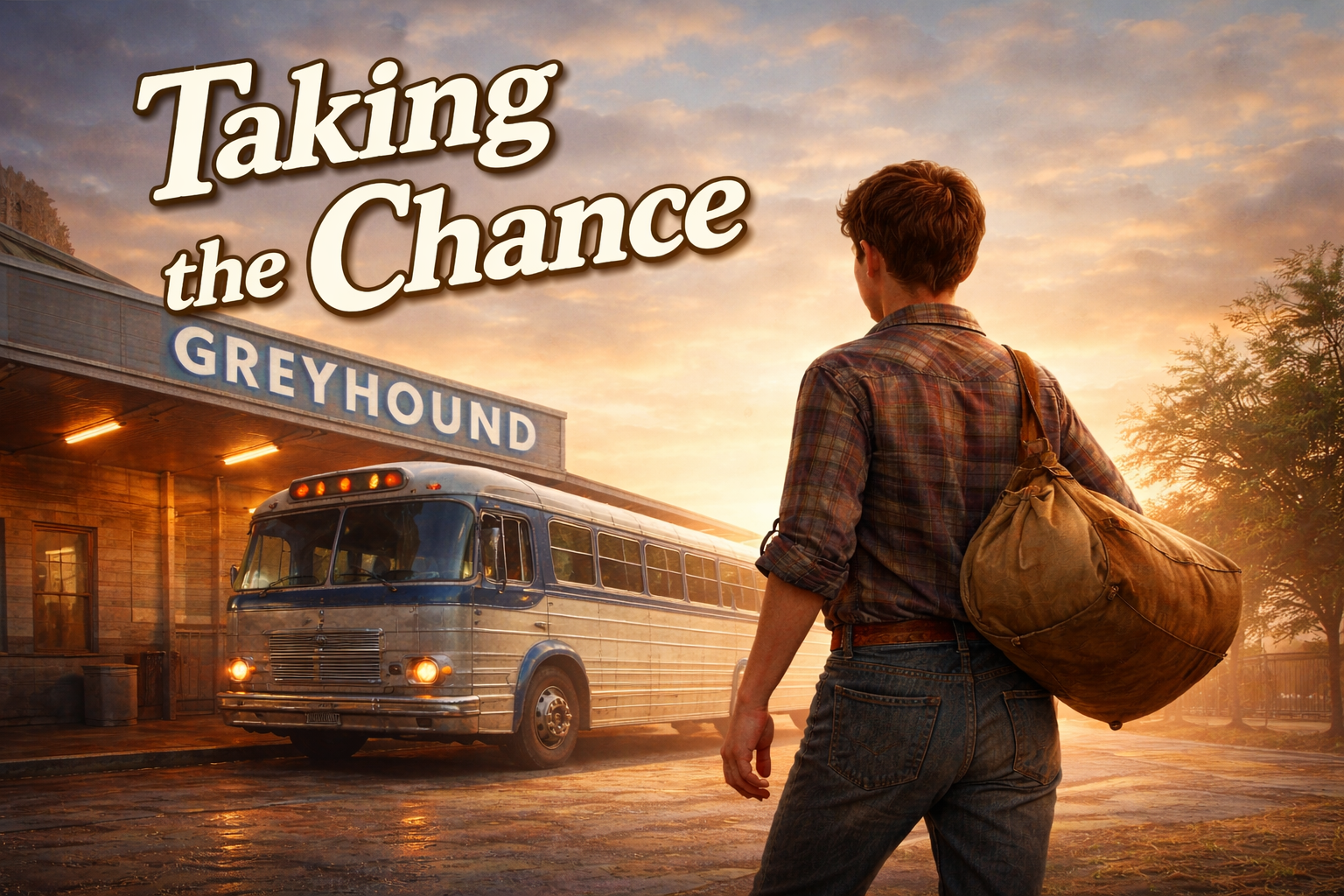

King’s Corner: Taking the Chance

At what point in life do you dare step out and take a chance, gambling everything? Most of us sense that we’re meant for some kind of adventure, but the moment to begin rarely announces itself. It usually arrives quietly—looking suspiciously like a bad idea.

For my dad, Mark King, that moment came early.

He dreamed of gold and silver, cowboys and Indians, horses and wide-open spaces. Growing up in a rough part of New Jersey and living with his mother, those dreams felt impossibly far away. When they argued, he’d sometimes “leave home” with great fanfare, only to quietly return a few hours later, once tempers cooled.

On his thirteenth birthday, another argument sent him packing again. He walked out the front door, then stopped just outside it, bag in hand, holding back tears. He was already calming down, already thinking about turning around. That’s when his mother came out, kissed him goodbye, and said confidently, “You’ll be back.”

That settled it. He wasn’t.

He went to the Greyhound Bus Station with $23 in his pocket and spent more than half on a ticket so changing his mind wouldn’t be easy. Where could $12 take him back? They rattled off destinations, and Fargo, North Dakota, sounded like it was way out west—and at that time, it was.

More than a day later, he arrived in Fargo, put his bag in a locker, and headed to a movie theater showing three cowboy films, including the newly released Stagecoach starring John Wayne. He watched them, trying to figure out what came next. He had achieved “out west.” The plan had not yet arrived.

Three boys came in and sat in the front row, talking. Mark struck up a conversation. When they asked where he lived, he said he’d just arrived and was looking for work. “Have you ever shocked wheat?” one asked. “My father’s hiring—five dollars a day, with room, board, and laundry.”

Mark started the next morning.

“Shocking” wheat meant stacking bundled sheaves after horses and sickles had cut them. It was hard, dusty work. Harvest lasted only a short time, and just as Mark began wondering what he’d do next, the man running the combine hired him on. One answered question created the next.

After that came work at a cattle and dude ranch in the Wapiti Valley near Yellowstone. They told him Theodore Roosevelt had once stopped there. Mark took to horses like a duck to water and soon led guests on overnight trail rides into the park. He was living the dream—and discovering that dreams tend to keep moving.

When the season ended, another decision waited.

A man came to buy a prized bull and twenty head of cattle and needed them delivered. Would anyone volunteer? Mark’s hand went up, even though he didn’t know where Perth was. He only knew it was far away, and by then that felt like the qualification.

The next morning, trucks headed to Seattle. From there, they boarded a tramp steamer bound for Australia.

The voyage took two to three weeks. Mark’s job was hauling eighteen to twenty buckets of manure morning and evening and throwing them over the side. His enthusiasm for adventure occasionally outran his common sense. When the buckets became encrusted, he tied one to a rope and tossed it overboard to rinse it. The bucket caught the water and began pulling him hard toward the stern. Just before he went over, several men grabbed him and hauled both him and the

bucket back in.

The captain was furious. If the rope had tangled in the propeller, he said, the ship would have been dead in the water in the middle of the ocean. “Do that again,” he warned, “and I’ll personally see to it that you go overboard.” Mark believed him.

They reached Perth, delivered the cattle, and Mark received a generous paycheck. Then he discovered there were no ships going back.

World War II had already begun overseas, though the United States had not yet entered. Australia, part of Britain’s Commonwealth, was under threat, and German submarines waited outside Perth Harbor. Mark had wandered into a war he knew almost nothing about.

Americans were helping quietly. They couldn’t be seen openly supporting Britain, so U.S. aircraft flew supplies to Australia, which then made their way onward. Mark had money but nowhere to go, and his great adventure suddenly felt very small.

He prayed the simplest prayer there is: “Lord, what do I do now?”

He ate daily at a café counter, where a kind waitress slipped him extra-large pieces of pie and listened. She introduced him to American airmen. One crew needed a seventh man for the return flight. Mark—still fueled by faith and nerve in roughly equal measure—talked his way aboard and flew from Perth to Milwaukee, where he could head west again.

He had taken the chance—again and again—often without knowing how things would turn out. Sometimes his courage outran his wisdom. But at every cliff’s edge, help appeared. Doors opened. And he learned that faith is often less about having a plan and more about trusting God when you don’t.

The question is whether the rest of us will dare to do the same—stepping forward when the way out isn’t clear, trusting that the God who meets us after the leap will also carry us home.

Jeff Headley is pastor of the Dayton Valley Community Church, and a storyteller who blends humor, honesty, and hope. His weekly column reflects on resilience, grace, and the surprising ways faith shows up in ordinary life.