How Dayton Helped Save Virginia City, Winter of 1889

We’re having a very warm, dry winter so far. That’s Nevada for you, extreme, unpredictable, and never quite the same year to year. Just a couple winters ago, many of us were snowed into our homes for days, some without power or heat. In my home, we are fortunate to have a wood stove. We hauled in buckets of snow to melt by the fire, cooked on the hearth, and I rigged a car battery to a solar charger and inverter so we could keep our phones powered.

We got through it with a little luck and a little ingenuity. And looking back, that stretch of hard weather has become one of my favorite winters, our family together, gathered around the fire for days, with nowhere to be but home.

Of course, Nevada doesn’t always bury us in snow. Some winters are more like this one. In fact, 1921 was famously warm: on December 12, 1921, Reno hit a record 69°F. But another record year, 1889 earned its place in history for the opposite reason; cold and snow. A lot of snow.

December 1889 is remembered as one of the harshest winters in Nevada’s recorded history. The Sierra reportedly piled up as much as 26 feet in places. You can imagine what that meant for Virginia City; snowed in, cut off from supplies, and dependent on transport that suddenly couldn’t reach the mountain town. With trains stalled, people began to suffer.

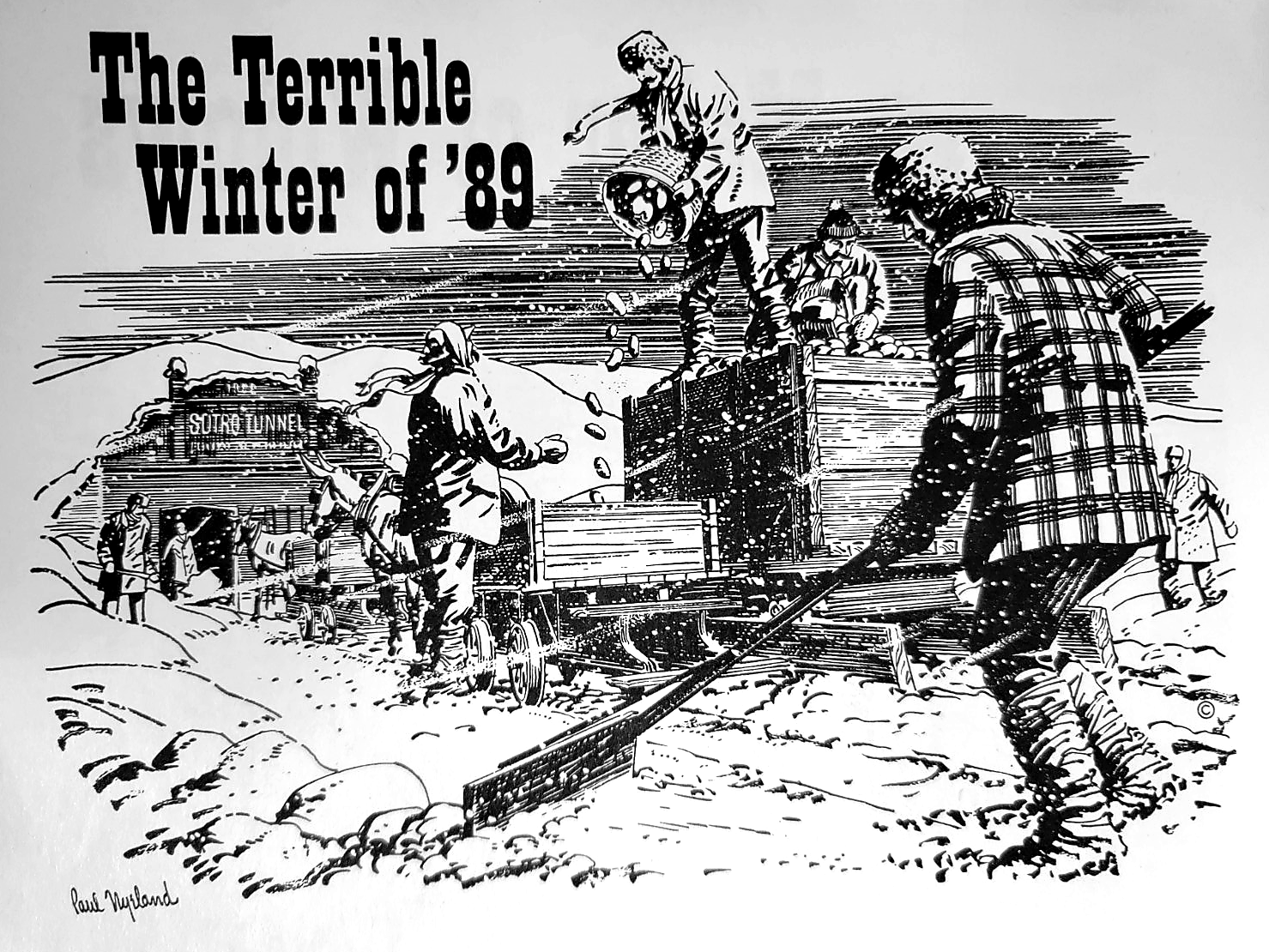

Then Dayton remembered something most of us still take pride in today, there was another way to help; the Sutro Tunnel.

I’ve heard many versions of the story of Dayton saving Virginia City by sending potatoes through the tunnel. The account below is one of the closest to what really happened. It comes from Pioneer Nevada (published in 1951, now public domain).

“SNOWFALL was early and heavy in December 1889, and Nevada stockmen were jubilant at the end of a “dry spell.” But the snow continued, and by mid-January train service at all Nevada points was at a standstill. From Wyoming west, the country was in the grip of a disastrous winter. Sheep and cattle starved and froze. Trains were stalled. The Sierras were blocked, as fires in the snow-sheds had left the tracks exposed.

A herd of wild horses, huddled and were frozen in their tracks near Virginia City. Cattle losses were 50 per cent. A band of 400 sheep froze in one night in Reese River. Everywhere mail was carried by sleigh and finally on snow shoes. Antelope bands starved at Wells and in Reno it was 42 below zero. One family drove 500 cattle to Elko by sleigh, but lost all the cattle and barely escaped with their lives.

All mines at Virginia City were closed as snow blocked the ore tracks, and food supplies ran so low the town was in danger of starvation. Finally, ranchers near Dayton ran sleigh loads of potatoes to the mouth of Sutro Tunnel. The potatoes were loaded into ore cars and underground trains hauled them to the C & C shaft. Tons of the “spuds” were lifted to the surface in Virginia City, amid the cheers of the populace.

In Reno the harassed Southern Pacific was caring for 600 unwilling passengers who were stranded, and the yards were jammed with snowbound trains waiting to get over the Sierras. For weeks the V&T, Carson and Colorado, and Eureka and Palisade railways had been snowbound. The roof of Piper’s Opera House fell in under six feet of snow. The 600 “guests” of the Southern Pacific at Reno petitioned for free rides back to Ogden and a detour through the Southwest to the Coast. The railroad stalled, until finally, on January 30, the tracks over the Sierras were clear and twelve locomotives began blasting on their whistles, calling passengers from hotels, saloons, and other points of local interest. Soon mobs of passengers jammed the Reno platform and filled the street as they hauled out baggage and loaded up. The townspeople cheered the passengers and the passengers cheered the trains, and at 1:30 in the afternoon the first of a long series of trains chugged out. It was a scene of great excitement, equaled only by the great Reno fire, and still later by the great Reno flood.

Meanwhile, the rest of the State dug itself out. Many cattle and sheep outfits were broke, bodies of animals littered the range for miles and commercial life was almost at a standstill. But the thaw continued and most stockmen were saved. Another week or so would have ruined the entire state. It had no real parallel in Nevada history until the dramatic winter of the Hay Lift, years later."