Alf Doten: The Man Who Wrote Nevada’s Memory

Sometimes a story lands in your lap and sometimes you’ve got to dig.

I never knew much about Alf Doten. Back when I first started digging into Adolph Sutro, I remember UNR and Ron James mentioning some of their findings on Sutro in the Doten journals, but the project wasn’t finished yet and they weren’t ready for anything to go public. So I tucked the name away in the back of my mind and left it there – until it all came flooding back.

If you’re into local history, get ready. Doten wrote about everything.

If you spend enough time around old mining camps and ghost towns, you start to notice something: for every loud, famous name on a monument, there’s usually a quiet one in the background who actually wrote everything down.

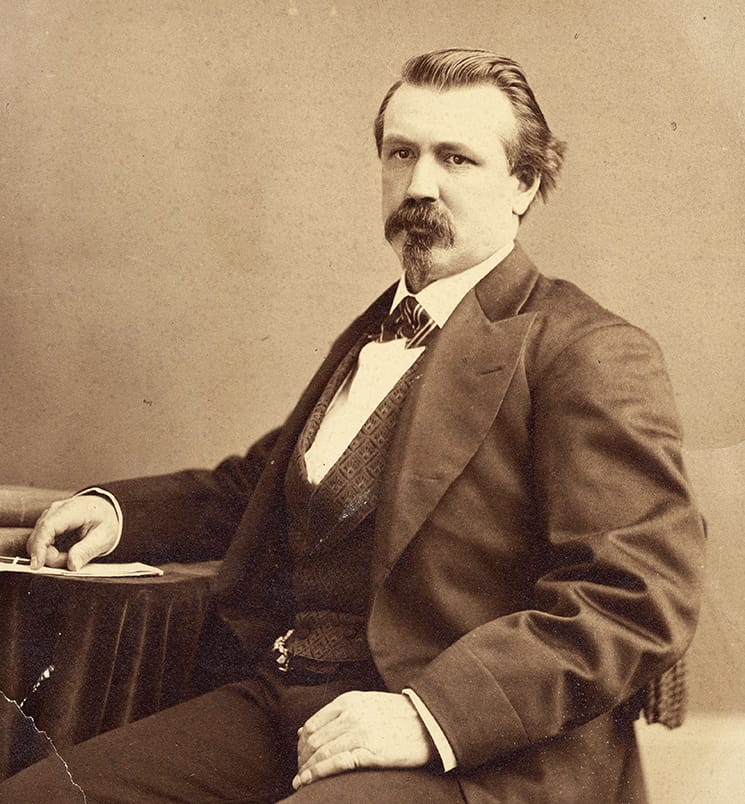

For Nevada, that quiet man was Alfred “Alf” Doten.

Doten was born in Massachusetts in 1829 and headed west in 1849 for the California Gold Rush. He tried mining, farming, and all the usual paths that either made you rich or broke you. What he ended up becoming was something different: a newspaperman and a compulsive diarist.

In 1863 he crossed into Nevada, taking work at the Como Sentinel, the little paper serving the mining camp up in the Pine Nuts above Dayton. I’ve been told countless times that Como was the county seat before Dayton. Turns out that isn’t true. Dayton/St. Mary’s was established as the county seat when Lyon County was created in 1861 and stayed that way until 1909, when the Dayton Court House burned down and the seat was moved to Yerington, in 1911.

From there, Doten moved through the heart of the Comstock: Dayton, Virginia City, Gold Hill, Austin, Eureka, Reno, Carson City. If there was a boomtown with a press, chances are Doten set type or wrote copy there at some point.

But his real masterpiece wasn’t a newspaper at all.

Starting the day he sailed out of Plymouth in 1849, Doten kept a private journal. He never really stopped. By the time he died in 1903, he had filled seventy-nine volumes with more than 1.6 million words. One entry per day, year after year, covering nearly every day of his adult life.

No big speeches. No polished memoir. Just weather, bar fights, funerals, mining deals, bad luck, good whiskey, and the kind of gossip a man usually only confesses to a notebook.

Nevada scholar Lawrence Berkove once said that “no detail was too trivial, no scandal too politically dangerous to be recorded,” and compared Doten’s journals to those of England’s Samuel Pepys. That’s not exaggeration. If you want to know what people in 1860s–1890s Nevada actually believed, not just what they put on public monuments, you will eventually run into Alf Doten.

This is where historian Ron James comes in.

For years, most readers only had access to an abridged three-volume edition of the journals, edited by Walter Van Tilburg Clark in 1973. That set is huge, but it still left out about 45% of what Doten wrote. The rest sat in Special Collections at UNR, locked away in the original notebooks.

Ron and a team led by Donnelyn Curtis at UNR took on the monster project of transcribing everything – every line, every scrap – plus nearly 4,000 notes to explain who’s who and what’s what. As of 2021, the full text is transcribed and checked. Their goal is to make the whole thing publicly searchable online so anyone, from scholars to curious Nevadans, can wander through Doten’s world.

Ron’s own article on Doten, “In Search of Western Folklore in the Writings of Alfred Doten and Dan De Quille,” makes a point that really stuck with me: Doten didn’t just record events. He accidentally preserved our folklore.

Scattered through those pages are little moments – horseshoes nailed over doors for luck, talk about Lake Tahoe “never giving up her dead,” old superstitions about numbers and dreams. None of these moments are big set-piece stories. They’re just Doten noting what everyone around him already “knew.” But put together, they show us the superstition, humor, fears, and hopes that everyday Nevadans carried around with them: miners, bartenders, judges, teachers, and all the others who passed through places like Dayton, Como, Gold Hill, Virginia City, and beyond.

Today, when we tell stories at the Odeon or talk about Dayton as Nevada’s oldest settlement, we’re walking in the same world Doten walked through. The difference is that he wrote it down in real time, ink on paper, day after day.

If Nevada has a memory, a lot of it lives in those 79 volumes.

Thanks to people like Ron James and the volunteers who finished the transcription, we now have a chance to meet Doten on his own terms - and to let his voice, and the folklore he preserved, back into our conversations about Dayton, Como, and the Comstock.

Please follow the link to begin your research into the Doten Journal, https://web.archive.org/web/20231003034302/https://clark.dotendiaries.org/